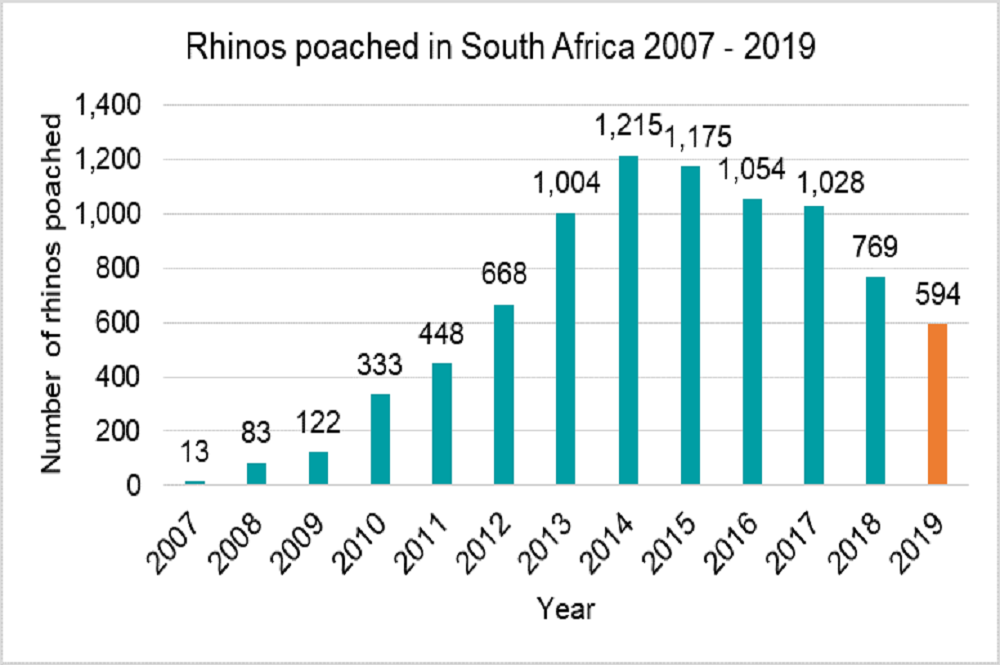

On 3 February 2020, South Africa’s Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries reported that a total of 594 rhinos were poached in the country during 2019. This is the fifth year in a row that poaching numbers have declined in South Africa, since numbers peaked at 1,215 in 2014.

The latest figures show a drop of 175 since 2018, a significant and extremely welcome decline. The numbers mean that on average in 2019, fewer than two rhinos per day were poached in South Africa. The latest figures continue the declining trend seen in the country since 2015, but what else do they point to?

Are all the anti-poaching tactics working effectively? Have the poaching crisis and recent droughts taken their toll on rhino populations? Are there now fewer rhinos left and therefore, are poachers less likely to find a rhino?

The number of incursions into parks and conservancies are not always reported, so it is hard to determine the long-term trends when it comes to the number of poaching attempts per area. However, in Kruger National Park – one of the places hardest hit by poachers throughout the crisis – there were 2,014 poaching incursions and activities in 2019, a 22% decline from the previous year. Thankfully, despite the huge number of attempts, only 16% were ‘successful’ (327 rhinos were poached), but this is still too many. Does this show that rhinos are getting harder to find? Maybe. It’s not clear without up-to-date rhino population figures (the most recent published South Africa rhino population numbers date from end December 2017).

The Provincial breakdown shows that there is not only more work to do within Kruger, but across the country. Kwa-Zulu Natal, for example, continues to see significant poaching, even with a decline in recent years. From our work with state parks and reserves in the Province, we know that rangers are extremely hard-pressed. We can only imagine what could happen if they weren’t on duty. But how much more successful would they be if they were properly trained, equipped and motivated – something our grants have tried to address, in the face of declining government budgets.

|

Provinces and National Parks |

2017 | 2018 | 2019 | % change (2018 – 2019) |

| Kruger National Park | 504 | 421 | 327 | -22.3% |

| Marakele National Park | – | 1 | 1 | 0.0% |

| Gauteng | 4 | 2 | 5 | 150.0% |

| Limpopo | 79 | 40 | 45 | 12.5% |

| Mpumalanga | 49 | 51 | 34 | -33.3% |

| North West | 96 | 65 | 32 | -50.8% |

| Eastern Cape | 12 | 19 | 2 | -89.5% |

| Free State | 38 | 16 | 11 | -31.3% |

| Northern Cape | 24 | 12 | 4 | -66.7% |

| Kwa-Zulu Natal | 222 | 142 | 133 | -6.3% |

| Western Cape | – | – | – | – |

| Total | 1,028 | 769 | 594 | -22.8% |

Reducing poaching has been at the forefront of all of our minds for more than a decade. Given the above numbers, this continues to be critical. But stopping poaching is only one of the actions required to save rhinos. We must simultaneously improve law enforcement so that when a poacher or trafficker is caught they are brought to trial promptly and sentenced appropriately if convicted.

We’re pleased to see that the Department’s statement also addresses some of these concerns: 145 people accused of poaching and trafficking were sentenced to at least two years’ imprisonment, with six individuals sentenced to 15 years. While this is a positive step, there were more than 332 arrests made in 2019, many more than the 145 sentenced. Given the large horn seizures in the country during 2019, improving enforcement is key to reducing illegal horn trafficking within the country.

Protecting rhinos is not easy. We know that poaching won’t stop immediately and we’re committed to driving poaching numbers down to negligible figures, however long it takes. The latest numbers are positive, but they are also a sign that without protection, rhinos could be in far more danger.

One of the long-term challenges of the ongoing poaching crisis is that it diverts attention, and donor funding, away from good biological management of viable rhino populations. Overstocking of a site can lead to increased mortalities, with many fewer rhinos being born and surviving, due to poor nutrition of breeding females. Missing such opportunities to maximise rhino growth is a real problem in some areas.

While anti-poaching measures are still a high priority, it’s important that we don’t forget the other tools in the box: biological management (including habitat management, range expansion and ongoing rhino monitoring), community engagement, capacity building, national and international coordination, and putting in place the long-term sustainable financing needed for Key 1 and Key 2 rhino conservation programmes.