As I said in my last blog, Entertainment Sumatran-Rhino-Sanctuary style, in September 2019 I spent a few days at the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary (SRS) in Way Kambas National Park, Indonesia, with my long-time friend and wildlife photographer, Nick Garbutt.

I blame / credit Nick for my mid-career switch to rhino conservation. After studying History of Art at university and 13 years of working for specialist art booksellers and publishers and finally for Tate, my husband and I did something completely out of character and signed up for a group wildlife trip to Madagascar. Author Jim Crace, whom I met via a freelance fundraising consultancy job, recommended that I read David Quammen’s book, The song of the dodo: Island biogeography in an age of extinctions, which talks about the Big Red Island’s lemurs and tenrecs, among many other species. So there I was, climbing up a mountain in the newly proclaimed Marojejy National Park, clutching a thick paperback while searching for silky sifakas and helmet vanga.

Our guide for that holiday was Nick. In those days, back in 2000, we were all still using film, and I was painfully aware that Nick was Usain Bolt when it came to changing rolls of 36 exposures, whereas I was somewhere at the back of the three-legged race. Whichever animal had usually been, done its thing and gone by the time I’d found it in my binoculars, let alone focused a camera lens on it. Nick’s massive enthusiasm and his love of wild places and wild animals led me to question my art-world focus, and to switch my fundraising energy into conservation instead. Nineteen happy years later, I’m still at Save the Rhino.

My husband and I have travelled with Nick many times, and we’ve become better photographers thanks to his tuition. But funnily enough, we’d never been to a rhino destination with him, until this visit to the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary. The deal was that he would be able to come with me, so long as he made his photographs available to us and to the International Rhino Foundation (IRF).

I don’t know about you, but I really love watching people at work who know what they’re doing, whatever that work is. When Nick is setting up a photograph, he’s intent, checking for the angles, deciding on the lens and the camera settings (no point and shoot going on here), and re-positioning props to create a more interesting composition.

Take a simple example: when we went to the local office of the Indonesian Ministry of Environment and Forestry, the rangers took us round the side of the building to show us the depressingly large collection of snares and illegal fishing nets they’d retrieved from Way Kambas National Park, together with some desiccated animal remains caught in the traps. Nice green wall behind; I took some pictures. Job done.

Nick, on the other hand, asked one of the Ministry’s rangers to pick up the snares and the withered skins in turn, to hold them up to the camera and look directly into the camera lens. With a wide-angle lens, aperture carefully chosen to blur the background, softened ranger’s face and sharp focus on his hands and the snare, it is unquestionably miles better than my effort.

I was a bit closer on another set-piece. We’d spotted that every morning, at around 08:30, one of the villagers would turn up at the SRS on a motorbike, completely laden with fresh-cut browse for the Sumatran rhinos to supplement that foraged from within their enclosures. The improbability of the size of the mountain of vegetation balanced on the back of the bike was wonderful.

Via Inov, the IRF’s Indonesia Rhino Manager, Nick explained to the villager that he wanted him to ride round the turning circle in front of the main SRS building several times, rather than stopping to unload. The sun kept going in and out from behind scattered clouds, and Nick needed the motorcyclist and the cargo to be in the right spot when the sun was not shining, or the reflections off the leaves would be too noisy (a serious case of the blinkies). Round and round the motorbike went, as Nick crouched behind the tripod, swearing softly every time the sun came out. Just as the load was starting to shed alarming quantities of twigs and leaves, the sun went in, the bike was on the right bit of the bend in the track, and the patient rider was looking directly at Nick.

(Currently, due to Covid-19, the browse is delivered only as far as the entrance to the Park, where it is washed thoroughly before being collected by SRS staff and taken to the rhinos.)

The most fun photo session was when we met up with members of YABI’s Rhino Protection Unit programme back at base. The day before, we’d gone on a boat trip towards the mouth of the Way Kanan River, to visit the departure point for their 15-day patrols through the Park. We’d asked them what they carried with them during these wild-camping patrols and now they were going to show us.

The two RPU members brought out a tarpaulin and spread it out on the veranda, before fetching their toiletry bags, sleeping mats, mosquito nets, cooking pots, head torches, GPSs, cameras and other equipment. Then they went to the kitchen and fetched a fortnight’s worth of rations: a very large quantity of heavy rice, noodles and cooking oil, packets of dried fish and spicy vegetables, a bundle of green beans, a bag of green and an even larger bag of red chillies, biscuits, and some pre-sweetened packets of tea. The pile of stuff looked far larger than the guys’ rucksacks, and that gave Nick an idea.

He set up the tripod, adjusted the camera angle, fiddled with the settings, and then explained, via Inov once again, that he wanted the guys to pack all the gear into the rucksack. The camera, meanwhile, would take a time-lapse image every second. Nick pressed go, stepped back, and asked Inov to signal to ‘go!’ Slightly bemused, the RPU team did as he asked (no doubt with the Indonesian equivalent of Mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the midday sun playing through their minds).

We’d caught the attention of the small knot of people waiting nearby for the hourly bus. Curious, they drifted nearer.

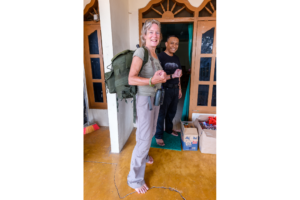

The guys continued packing, long experience having taught them which order to follow, which side pocket to use, what could be tied onto the outside. Buckles were fastened; straps tightened. About quarter of an hour after starting to squeeze things into the rucksack, one of them put a shoulder, then the other, through the harness, shrugged it on, tightened the belt loop, stood up, and made to march off.

Now for the magic. Nick set the camera to replay the images as a film, and then motioned the RPU members forward to watch. Clearly not knowing what to expect, they leant in, and watched mesmerised as the 10-second film played, then burst into laughter. They wanted to see it again, then let the rest of us watch while they went to wake up the rest of the team from a sultry afternoon’s siesta. Helpless giggles all round.

The bus queue wanted to see what we were all laughing at. Nick happily obliged.

In normal, non-Covid-19 years, there would be official visitors every couple of months; no doubt the RPUs would take people out onto the river and into the forest, just as they’d done with us. The visitors would ask questions, translated by Inov, and the RPUs would reply. Perhaps too shy or polite, or perhaps because Inov had briefed them in advance, they didn’t ask us our reasons for being in Sumatra, but patiently answered our questions and posed for photos.

What I loved about this particular photo session was that it felt as if we were giving something back to the rangers who work so hard to monitor and protect Way Kambas’s Sumatran rhinos and other wildlife. Yes, our grants will help pay for salaries and rations (even more of those chillies!), fuel for the boat and the motorbikes, batteries for the torches and GPSs. You can’t conserve Critically Endangered rhinos without cash after all. But conservation also needs the rangers in the field to put up with the discomfort of camping in insect-blown forests, to patrol day after day, to care about their work. We’d made these guys laugh, and that felt really, really good.