As big and bold as they are, rhinos aren’t that easy to find. This has its pros and cons; a pro being that it makes it easier for a rhino to evade being poached, and a con being that it makes it harder for rangers to keep track of them. This con is especially hard when you’re looking for black and white rhinos in a 60,000-acre undulating and partially forested landscape. That’s what it’s like at Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Kenya’s Meru County that was established in the 1980s.

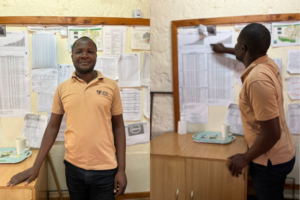

Thankfully, there are experts at Lewa who know a lot about tracking rhinos. People like William and Gitonga, two rangers who are stationed at the Conservancy’s Samburu outpost. Samburu is just one of the strategic bases at Lewa that’s home to the Conservancy’s on-duty rangers (often two or three people) for four weeks, before they rotate with a colleague and enjoy time away from work to spend time with friends and family.

While on duty, rangers like William and Gitonga spend their daylight hours tracking rhinos in their area, and they’ve come to learn the local ‘who’s who’. They do this mostly by recognising the notches on the ears of adult rhinos. Each notch represents a different number, which add up to provide an individual’s unique ID. Once they’ve established the rhino’s identity, they record the time, location, behaviour, and overall health and condition of the animal, before reporting back to HQ.

All recent sightings and related information are shared with resident Lewa rhino expert, or, to give him his official title, the Rhino Monitoring Officer, Ken Onzere, who joined Lewa in 2019. Ken collates the field data and uses it to track Lewa’s rhino population over time. Such information helps to manage the rhino population, ensuring rhinos are healthy and breeding successfully, and provides the evidence needed for operational decisions, such as future ear notching procedures, rhino translocations, or potential feeding strategies.

It’s thanks to this stringent data collection that Ken can predict future population changes fairly accurately. For example, 2019 was a significant year for new rhino calves. But, with an inter-calving period of two to five years, it was likely that births in 2020 and 2022 would be reduced. So far, Ken’s predictions have been correct. Next year, however, is set to be a big year for rhino calves. Like rhinos hiding in the landscape, this too has its pros and cons.

New calves mean more rhinos, which is exciting and important for conservation. Yet, more rhinos means more animals to identify (one ear notching operation costs around $2,000) and for rangers to find each day.

Thankfully, recent grants have been supporting rangers, so that after a tough day of patrols, they can at least enjoy some comforts back at base. At the Samburu Outpost, William and Gitonga now have electricity, thanks to solar power recently installed from a grant by the ForRangers initiative. This power means that there’s no more coming back home at night to a dark room with a kerosene lamp. Each room now has lights and sockets to charge phones and other electrical items. And this is just one of the ways that ForRangers provides support for the people that, as John Pameri, Head of General Security at Lewa, says, are “the eyes and ears on the ground.”

ForRangers also funds the life insurance policy for William and Gitonga, and their colleagues, ensuring that they, and their families, have financial support should they be injured, or worse, in the field. Given the tough job they all do, spending hours out in the bush among wild animals and difficult terrain, and sometimes facing armed poaching gangs, this insurance is essential.

Since 2020, ForRangers has funded a group insurance policy, initially covering more than 1,000 rangers in Kenya, and now extending to more than 3,200 rangers across 62 protected areas in 11 African countries. With more than 100 rangers being killed on duty each year, and many more injured, insurance like this is vital to give rangers like William and Gitonga, and their loved ones, the support they deserve.

This July, we’re raising funds to support this vital insurance scheme, which costs approximately £36 per year for one ranger. If you can, please donate to support this appeal today.